What Next for Financial Planning in the UK

INTRODUCTION

Business owners are forced to consider the unknowable future, at least periodically, if they want to stay relevant. This is one of the biggest challenges in running your own show.

I love a good prediction for the future of financial planning as much as the next person. However, as we know, trying to foresee the future is fraught with peril.

Don’t misunderstand me. All contributions that speculate on the future of the profession are helpful in that they get us thinking, questioning, debating and discussing. However, a well-crafted paper that gets us believing we can see the future might be just as dangerous as one that is complete nonsense.

My objective in this white paper is to add to the conversation.

THERE ARE A FEW WAYS TO ACCESS THIS WHITE PAPER:

- Listen to a full audio version of this white paper on Spotify, below.

- Download a PDF version to read at your convenience by submitting your email address, below.

- Scroll down through each section right here on this page.

Sign up below for instant access to the PDF version of this white paper

Fill in your details, below, and we will send you a PDF version of the white paper to read at your convenience.

WHY I WROTE THIS PAPER

I’ve been thinking hard about the next iteration of the financial planning profession.

Why?

There are several reasons

- 1. I Iove the financial planning profession and want to see it continue to grow.

- 2. In my mind, financial planning should be the dominant, winning business model.

And while financial planning is certainly gaining traction with advisers around the world, it would be hard to describe it as dominant. Old school business models still control the bulk of global wealth and capture the largest share of clients minds and wallets.

Financial planning is not known or understood in any meaningful way across society. (Just ask your parents or friends “What is financial planning?” for confirmation)

- 3. I’m a business consultant who helps emerging financial planning firms become successful and resilient businesses.

I need to have my eyes on the future if I’m to continue to do that credibly and effectively

- 4. I’m curious (as I’m sure you are) as to what might ‘make’ or ‘break’ an amazing, client-centric business model.

WHAT CONCERNS ME

I’m worried that with the pace of technological change and the increasing power and reach of the biggest tech companies, that our cushy, beautiful business model might get disrupted before it ever achieves the heights that we all want to see it hit.

As I’ve contemplated how to think about these issues, the model I’ve found most useful is what The Economist called “one of the six most important books about business ever written”*, The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen.

Let me try to give a simple explanation of Christensen’s work. It goes without saying that I can’t do it justice in a few paragraphs or pages and I strongly recommend you read the book yourself if you find this paper interesting and relevant to you and the future of your business.

* “Aiming high”, Jun 30th 2011. The Economist

THE INNOVATOR’S DILEMMA

The central question Christensen sought to answer was “Why is success so difficult to sustain?”

He was a Harvard Business School academic who wanted to understand why dominant players in many industries eventually failed and went out of

business, or lost their once-dominant status.

Let me give an example using the US car industry.

In 1957, when Toyota enters the US car market, they are a little known Japanese company that makes small fuel-efficient vehicles.

In the US, the big three (GM, Ford, Chrysler) make large gas-guzzling motor vehicles for a country that is geographically large with a relatively low cost of fuel.

The mass market doesn’t buy smaller fuel-efficient cars.

So the big three don’t defend the low-end space. Why would you?

As a result, Toyota gains an industry foothold pretty much unopposed.

50 years later they become the number one carmaker in the US.

Christensen’s theory would argue that based on everything the leaders of GM, Ford and Chrysler knew and had been taught at business school, they did the right thing by choosing not to play in the low margin, low oxygen environment of small vehicles when Toyota first appeared.

They were listening to their customers, as we’re all encouraged to do, and their customers were not asking for smaller fuel-efficient vehicles.

By ignoring Toyota’s first move, the established carmakers allowed a disruptive competitor to gain a foothold. Disruptors can do this in a new market with a smaller scale of operations and therefore can survive on much smaller revenues and margins while they figure things out.

I use the car industry as one example. Christensen’s research used the computer disc drive industry as his focus of study because its cycle time for new innovations was the shortest. If you’re old enough to remember, about every 2 years a new computer storage disc would be released that replaced previous versions; usually smaller, yet holding a lot more information.

Clearly, in more capital-intensive industries (like cars), the cycle time for disruption could be longer (decades rather than years). Although, look at Tesla and the impact it’s having on the automobile industry.

Here’s a quote from Larissa MacFarquar in The New Yorker, May 7, 2012:

“Christensen discovered, the new technologies that had brought the big established companies to their knees weren’t better or more advanced—they were actually worse. The new products were low-end, dumb, shoddy, and in almost every way inferior. The customers of the big, established companies had no interest in them—why should they? They already had something better.”

This is the essence of the Innovator’s Dilemma.

At one level it is entirely logical for established players to ignore the new entrants who seem to be playing for low stakes in markets the incumbents don’t want to play in.

However, their failure to take action is what sows the seeds of their eventual demise.

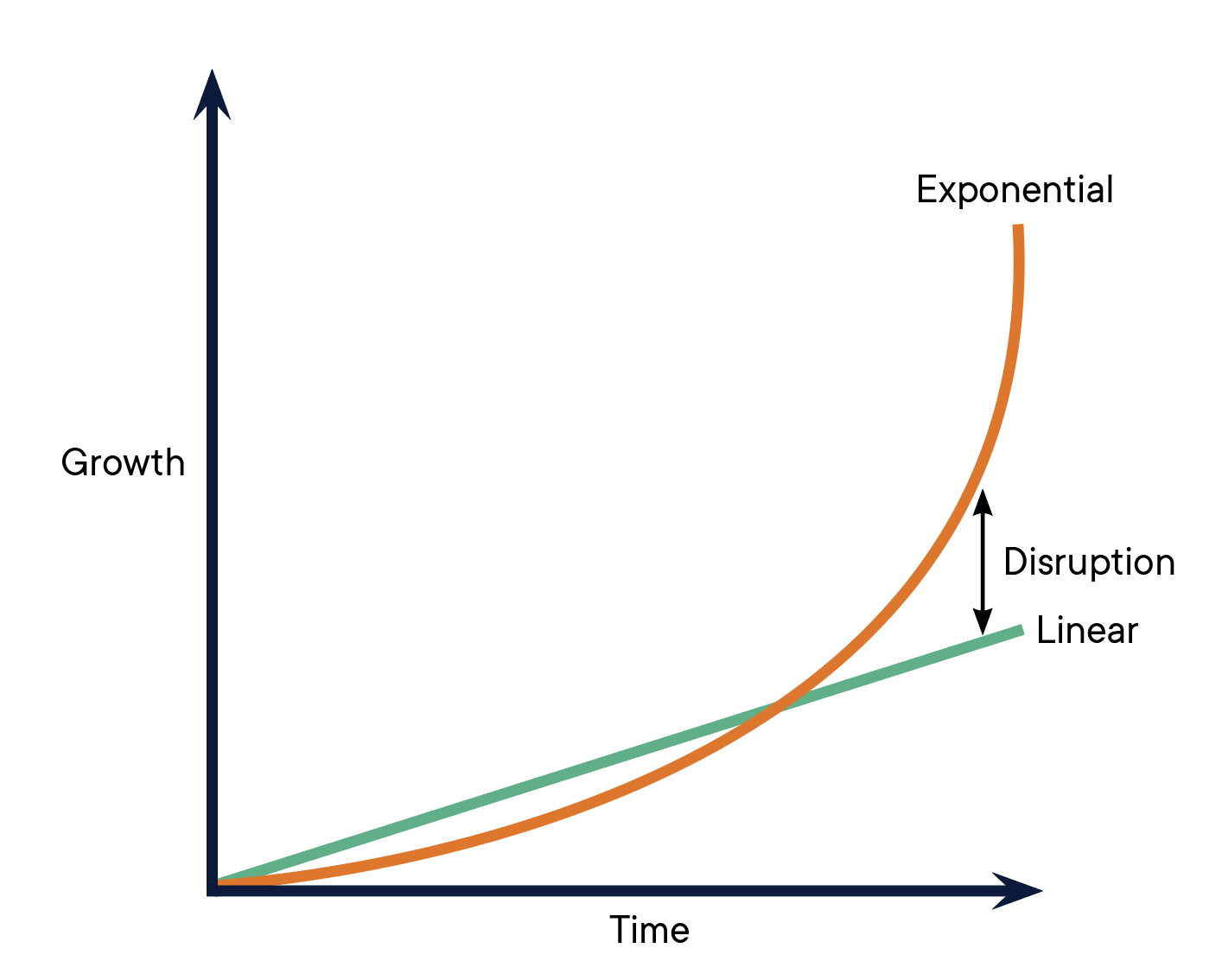

We can see this happening in financial advice around the world right now. I’ll return to this theme shortly, but first I want to highlight one of the key attributes of many disruptors. That is, they grow exponentially and so no one sees them coming until it’s too late

LINEAR VS EXPONENTIAL GROWTH

Some of the new entrants into the financial advice space are technologically driven businesses that have the power to grow exponentially if their business model works.

Peter Diamandis, best known as “founder and chairman of the X Prize Foundation, and co-founder and executive chairman of Singularity University” believes our brains are linear in an exponential world.

Here’s a simple example he uses to make the point:

If you take 30 linear steps where do you end up?

30 metres away.

If you take 30 exponential steps how far will you travel?

1 billion metres or 26 times around the world.

Online businesses can grow exponentially and herein lies a potential threat that we’re unlikely to see coming because of the way our brains are wired.

The graph below highlights the problem.

* Wikipedia

Due to the exponential nature of disruption, new entrants can appear more of a joke than a threat for quite a long while.

However, 1 becomes 2, becomes 4, becomes 8, becomes 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 etc.

Most people know the story of Kodak’s decline.

“In 1975, Kodak engineer Steve Sasson created the first-ever digital camera. [It] was about the size of a breadbox and it took 23 seconds to capture a single image. It took 0.01-megapixel images shot only in black and white that were saved to a cassette tape.” *

Not particularly handy I’ll admit, but Kodak missed the point.

The slow initial development of an exponential technology deceived them into missing it’s future potential and eventually it put them out of business.

This is an important point to note for all financial planners. You can be deceived by the slow going of your disruptive competitors in the early part of the process.

* Indianexpress.com – Timeline: The evolution of digital cameras, from Kodak’s 1975 digital camera prototype to the iPhone

THE CHALLENGE FOR FINANCIAL PLANNERS

Let’s go back to the Innovator’s Dilemma.

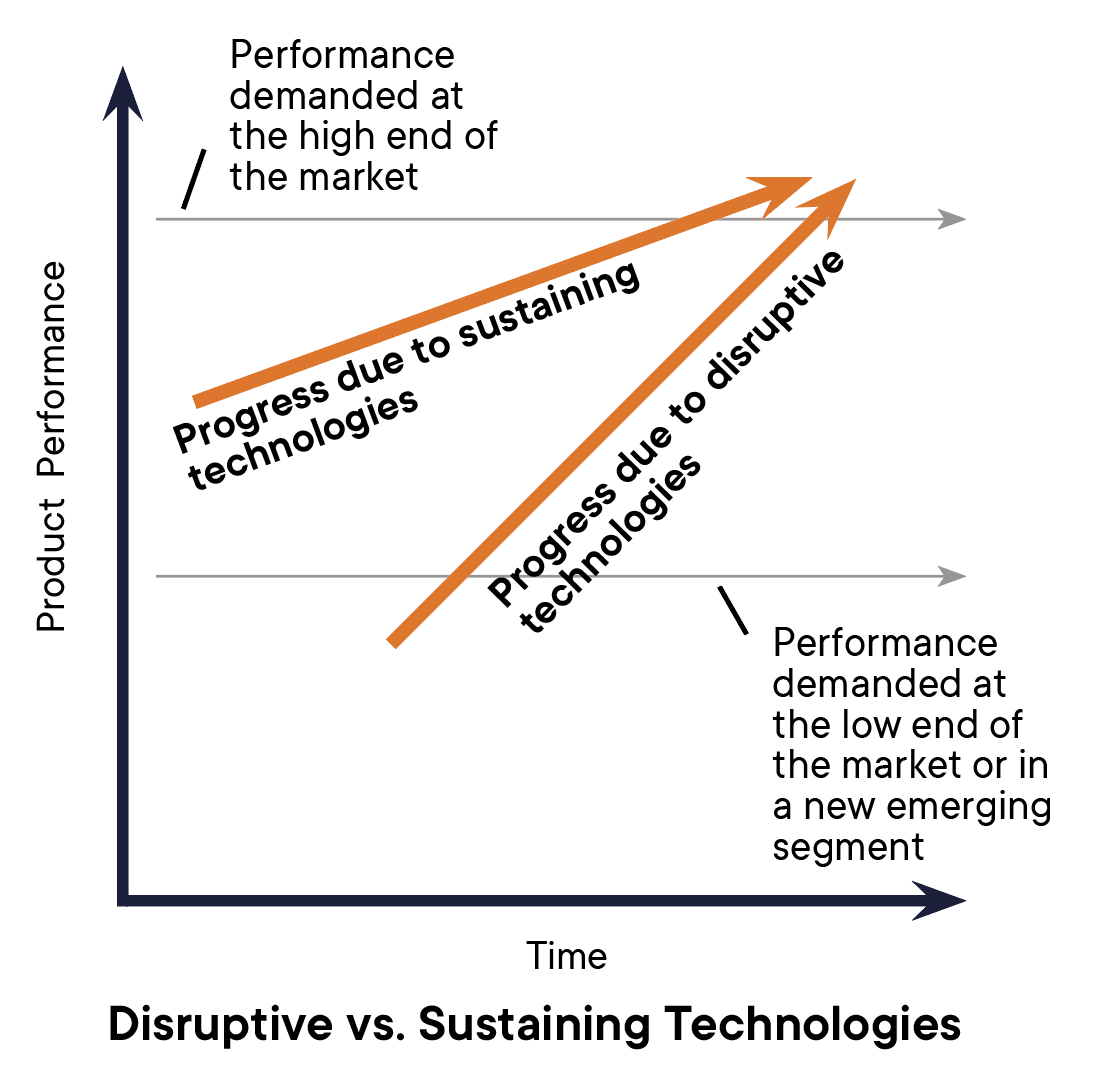

There are two important definitions from Christensen’s work I would like to highlight; sustaining technologies and disruptive technologies.

Sustaining technologies advance the current business model’s delivery to existing customers. Basically, they let you do what you currently do, but better.

Disruptive technologies do something different (often worse) for an unserved or seemingly unprofitable group of customers, often at a poor margin.

It’s important to understand these definitions, as almost anything that’s new is labelled by the mainstream media (often incorrectly) as disruptive.

Most of the innovations Christensen researched in the disc drive industry were sustaining innovations. Relatively few were truly disruptive according to his definition.

So, if we apply this to financial planning, how would you categorise cashflow modelling tools like Voyant, Truth/Prestwood and Cash Calc (I’m using UK tech examples)?

To me they’re clearly sustaining innovations, allowing you to do what you do already, but better.

A disruptive technology might be what we call Robo-advice, “something different (often worse) for an unserved or seemingly unprofitable group of customers, often at a poor margin.”

Author’s Note: Whether Robo’s do end up disrupting things remains to be seen

The following chart from The Innovator’s Dilemma captures the challenges incumbents face. And let me use financial planning as the example here just to make it relatable.

The top horizontal line in the chart shows the performance demanded by clients at the high end of the market.

The darker upward tilting line that starts below it and eventually crosses it, shows progress due to sustaining technologies.

One might argue that 25 years ago the emerging profession of financial planning was earlier on that darker upward line and below the performance demanded at the high end of the market.

As improvements were made to the way financial planners did their job, for example using cashflow modelling and wrap platforms, and new services were added to the mix, I believe that the best financial planning firms meet or exceed the performance demanded from the high-end clients that they serve.

Christensen argues that adding new services above this level will yield no real benefits for the incumbent firms. Clients won’t pay more for things they don’t want or need. So adding to the existing service becomes a drain on profitability.

The more vertically angled line shows progress due to disruptive technologies.

As you can see, a new disruptive technology may not even meet the minimum level of performance demanded by the low end of the market when it first launches.

However, playing in this low oxygen, low profitability space unopposed allows new entrants time to find out where their disruptive approach might resonate best; the fail fast approach*, espoused by tech companies.

Like Toyota in our car example, once the disruptor does gain a foothold at the bottom end of the market, they can start to move into the next level and over time become genuine competitors for the established players.

If we assume that in today’s world new entrants are also digital and have the ability to grow exponentially (if successful) then they can fly below the radar initially, yet become a major threat suddenly as they gain traction.

This is the well-trodden path of disruption

* Fail fast is a philosophy that values extensive testing and incremental development to determine whether an idea has value. An important goal of the philosophy is to cut losses when testing reveals something isn’t working and quickly try something else, a concept known as pivoting. Source: WhatIs?.com

IS THIS ALREADY HAPPENING TO FINANCIAL PLANNING?

If I think of all the smaller boutique firms that deliver high-quality financial planning advice as one larger business (and some may argue this is a bit of a stretch), I can see that we might already be some way through the disruption cycle.

While pure Robo-advice hasn’t knocked us off our perch (yet), there are moves afoot that suggest it could gain more traction.

In the UK Nutmeg was recently sold to JP Morgan “to form the basis of the bank’s digital wealth offering outside of the US” *, while abrdn has acquired AI-driven wealth management solution Exo Investing, with the intention of providing “24/7 digital wealth management” via an app.”

In the US market itself we’ve seen the rise of what Bob Veres, publisher of Inside Information, calls Cyborg Advice; a blend of human and robo. Some of the players in that space include Schwab and Vanguard. Clients can receive advice on the phone or via video conference from these major brands and any client money will be invested using some underlying robo-style technology.

Spring 2021 saw Vanguard launch this style of digital-advice into the UK market.

It might not be what you and I consider financial planning, but it’s a significant development and is opening up advice to other market segments often not served by existing financial planners.

* Funds Europe: JP Morgan buys Nutmeg

WHY SHOULD YOU CARE ABOUT THIS IF YOU’RE AN OWNER OF A FINANCIAL PLANNING BUSINESS?

It’s a good question.

Stick with me for a quick potted history of financial planning. It’s important to know that history if you want to understand where your business sits in the world today.

Financial planning’s official birth took place in the US, on December 12, 1969, in a hotel meeting room near Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. Organisers, Loren Dunton and James R. Johnston, had contacted everyone they knew in financial services, but only 11 men showed up including insurance salesmen and salesmen of mutual funds and securities. One financial consultant and one publicist also attended.*

It reached my home market, Australia, in the 1980s, so I’d put us in the early adopter category in Australia, but certainly not in the pioneers. When I migrated to the UK in April 2004, the first cohort of financial planning firms were just starting to break through and the initial growth came in the decade after I arrived with the advent of viable wrap platforms, that allowed advisers to construct and manage truly independent investment portfolios and select their own level of remuneration. It was the catalyst that started a trickle that became a flood, spurred on in 2012 by the Retail Distribution Review (RDR)

Over the years, more and more advisers have discovered the joys of running a truly client-centric business model. The most successful exponents have become more sizeable players in the UK marketplace, although they are still dwarfed by the major old school brands and wealth managers. Firms like Paradigm Norton, Cooper Parry Wealth, and Carbon Financial Partners have demonstrated the management quality to grow and expand significantly.

So, financial planning is a model that’s 50 years old from inception and probably 30 years old from more mainstream adoption. It’s not new.

My point is this. If you’ve recently discovered financial planning as a business model, you’re catching up, not breaking new ground.

The world is changing and changing fast and the biggest threat to the future of financial planning is complacency or smugness and a belief that we’ve got it all figured out.

* The History of Financial Planning – The Transfomation of Financial Services. By E. Denby Brandon, Jr. H. Oliver Welch

IT’S NOT ALL DOOM AND GLOOM

I often hear arguments against the demise of financial planning. Proponents tell us that artificial intelligence (AI) will never replace a human who can ask great questions, listen with empathy and guide or coach people to making better decisions.

I want to believe it. Really, I do.

Tyler Cowen, the American Economist has an interesting view on the future of employment in his book, Average is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation.

Many pundits predict a major decline in employment due to the rise of AI and other technologies that will take over from humans.

Cowen gives an alternative and more nuanced view using freestyle chess as an example.

In freestyle chess, teams of players are allowed access to a computer before they make a decision on their next move.

We know that in 1997 Gary Kasparov, the world chess champion at the time, lost to the IBM computer Deep Blue, the first time a machine had beaten a chess grandmaster. And despite Kasparov winning the series 4-2 he was defeated the following year by Deep Blue in a rematch.

So, in 1997 a machine is now better than a human at chess.

However, here’s Cowan’s insightful observation.

In freestyle chess, a team of three or four good regional or national standard players, plus a computer, can defeat the computer on its own.

So, a team of people plus a machine is now better than a machine on its own at chess, even without a grandmaster on your team.

Cowen’s belief is that in the workplace, this approach of humans plus machine learning could see us reach new levels of excellence as well as making the predicted mass redundancies less prevalent than some pundits fear.

While I’m not going to wade into predictions about future employment trends, I like this way of thinking as a model for how financial planners might thrive and prosper in a world being disrupted by an ever-increasing range of exponential technologies.

We can already see that some of the Robo-technologies that are not (yet) disrupting the investment space might become very handy tools for financial planners to use in improving their own productivity. So humans plus machine learning might be better than the machine on its own, just like in freestyle chess.

Maybe the proponents of the view that “artificial intelligence will never replace a human” are onto something.

But…

Whilst Cowen’s view might be comforting, two other questions keep swirling around my brain:

- 1. What if we’re wrong?

- 2. Cowen’s approach doesn’t fully deal with the Innovators Dilemma that Christensen has alerted us to

OK, SO WHAT SHOULD WE DO?

Let’s get honest with ourselves. Financial planning is the preserve of the wealthy, at least in its current form.

By and large, as a profession, we serve the top 9% – 10% of the wealth tier (and that might be optimistic, it could be the top 5%).

That leaves the other 90% of the population – the blue ocean as W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne called it in their 2004 book Blue Ocean Strategy – ripe for potential disruptors to work with uncontested.

Players like Ant Group, Facebook, Apple, Google and Amazon are amassing reams of data on users and supplying low-level financial services to the blue ocean.

I don’t even know how to quantify the threat from players of this size and scale.

I realise we’re not trying to compete against these players in a direct sense, but our challenge is to stay relevant and to create businesses that can survive and thrive for the next 20 years, regardless of what developments challenge the status quo.

I believe there are different strategies that will be appropriate for the different types of financial planning firms, which I’m going to categorise as:

a.) Larger successful financial planning firms that want to be around for the

next 20 years+.

b.) Adviser-owners approaching the end of their career.

c.) Adviser-owners who have just discovered financial planning

A.) THE LARGER FIRM STRATEGY

If I was running a successful financial planning business I would take a lead from Clayton Christensen, who developed the playbook for dealing with the threat of disruption.

1. Christensen says: Develop the disruptive technology with the ‘right’ customers. Not necessarily your current customer set.

For financial planners, I believe this means finding ways to work with the next generations of clients; millennials and Gen Z.

And I don’t mean fooling yourself by offering a free financial plan to the children of your wealthy retired clients either. That’s not what I’m talking about.

I mean starting with a blank piece of paper, doing some research and listening to the next generations about what’s important to them personally as well as financially. That’s the starting point.

2. Christensen says: Place the disruptive technology into an autonomous organisation that can be rewarded with small wins and small customer sets.

If I was running one of the larger more successful financial planning firms, I’d be selecting a few of my best and brightest young, up-and-coming employees, to set up as a separate business and task them with creating a financial planning firm for their mates.

I’d allocate some limited start-up capital for them to get going with.

I’d locate it outside of my current business premises to facilitate greater autonomy and independent thinking.

Their break-even point for this new enterprise is tiny compared to the existing business, so they can survive on small wins as they find their feet.

3. Christensen says: Fail early and often to find the correct disruptive technology.

By keeping my experiment small with my autonomous team and start-up, they’re free to pivot as often as necessary and to run a larger variety of experiments to find where the real needs of their clients are and to craft a solution that can work commercially in serving that need.

4. Christensen says: Allow the disruption organisation to utilise all of the company’s resources when needed but be careful to make sure the processes and values are not those of the company.

By keeping the start-up autonomous, the young team can develop their own values and processes.

However, when they ask for input or support (intellectual, technological, or financial) they can leverage off the larger organisation. Matthew Jackson and Bob Veres have dived deeply into the journey that industry-leading firms will need to embark on in their paper, New Frontiers In Wealth Management. I highly recommend a read if you’re a larger financial planning firm

B.) THE END OF CAREER STRATEGY

I’m going to provide two options here depending on how your head and your heart are feeling at the end of your career.

Option 1 is for those who are worn out and feel like they’ve done everything they wanted to do in their career.

I’d be looking for a buyer. You can decide what suitable buyers for your business look like.

Option 2 is for those who are still excited about the future OR are a little frustrated and fearful, but open to ‘going again’. (You can download my free Guide To Going Again here)

For anyone who feels like Option 2 is a possibility, the challenge is to re-set and select a big hairy audacious goal (BHAG) for the next 10 years.

I don’t care if your time horizon is only 5 years or 7 years. Set a BHAG for your organisation and get after it with 100% commitment.

What I’ve seen is that adviser-owners who do this can not only get a new lease on life for the final phase of their career, but they also add a ton of financial value to their business.

Typically these option 2 firms will have a successor (or successors) lined up internally and that’s why setting a BHAG for the organisation is important.

Although you might step off the bus in 5-7 years time, your successors will be well established to continue the mission after your departure.

If for any reason the succession plan fails, you can still sell the business.

That option is always on the table. However, businesses with viable successors in place sell for higher multiples in my experience than those that are just selling a book of clients.

C.) THE JUST DISCOVERED FINANCIAL PLANNING STRATEGY

Typically, there are two reasons why you’re new to the financial planning model.

The first is that you’re a younger adviser who has started their own business in the last few years.

The second is that you’re an older experienced adviser who has only recently decided to make a transition from the older school more transactional business model into the financial planning-based model.

In either case, the strategy for me would be the same.

Your focus has got to be on laying solid business foundations. Don’t be perturbed after reading this white paper that the sky is falling. It isn’t.

And while there are threats and concerns you need to be looking out for, right now you have one priority, which is to create a solid support team and business structure around you.

If you can get that nailed over the next few years, THEN you can start evaluating your next steps and strategic options.

To start worrying too much about future threats before you’ve established your current business would be a mistake.

COULD I BE WRONG ABOUT THE THREATS AND WORRYING UNNECESSARILY?

Yes.

If I’m wrong and worrying unnecessarily, a strategy of incremental improvement is just fine. Keep doing what you’re doing and just do it a little better each year.

However, I could also be wrong on the other side of the coin; underestimating the pace and extent of the disruption that’s headed our way. Perhaps it will occur even faster than any of us has contemplated. After all, we’re the incumbents and turkey’s don’t vote for Christmas do they?

LET’S FINISH WHERE WE STARTED

No one knows the future. The thoughts I’ve outlined here are probably as valid or invalid as anyone else’s.

My goal is to add something to the conversation for the benefit of everyone involved in the mission to make financial planning the dominant business model.

What do you think?

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Please feel free to drop me a line via [email protected]