If Incentives Worked, We’d All Be Amazing By Now

INTRODUCTION

Do you run a financial planning firm where some (or all) of your team members are ‘incentivised’ to do their best work?

Maybe you don’t own the business yourself, but work in an environment with incentives in place if you behave in a certain way or achieve certain outcomes.

In almost 35 years in our ever-changing profession, I’ve seen all sorts of incentives put in place in the belief that this will make people do a better job, or keep them focused on what really matters.

As I’ll outline shortly, this belief that incentives are an important part of motivating people (particularly in selling roles) is almost part of our profession’s DNA.

But what if incentives don’t do that? (Blasphemous, I know)

Could our beliefs be misplaced, or just completely wrong? What then?

In this white paper, I’m going to delve into the pros and cons of incentives; do they actually work, and if they do, under what circumstances?

Do they help deliver the outcomes advice firms want them to? If not, what are the alternatives?

The evidence shows that incentivising your team may actually lead to outcomes that you don’t want, and fail to achieve the outcomes you thought you did want.

That might be confronting, but I’d ask you to read (or listen to) the whole argument I’ve made here and test it against your real-world experience as:

● A business owner or operations manager who has implemented incentive schemes,

or

● As an employee who has been on the receiving end of them.

Maybe it’s time for a change of approach.

After all, we’re rapidly becoming a profession and trying to build genuine professional services firms. And in those types of businesses, there’s only one goal:

Do what’s best for the client every time.

The BIG question is: Do we need incentives in place to get the people who work in our profession to do that?

In fact, is it even possible to incentivise people to behave in that way if it’s not already in their nature to do so?

Or should we just hire people who already think and act in that fashion and forget the incentives?

THERE ARE A FEW WAYS TO ACCESS THIS WHITE PAPER:

- Listen to a full audio version of this white paper on Spotify, below.

- Download a PDF version to read at your convenience by submitting your email address, below.

- Scroll down through each section right here on this page.

Sign up below for instant access to the PDF version of this white paper

Fill in your details, below, and we will send you a PDF version of the white paper to read at your convenience.

The power of history (or ‘but we’ve always done it this way’)

In the UK (and many other markets), financial planning as a profession evolved out of the old hard-core sales culture of the insurance industry.

In the insurance era, ‘agents’ sold insurance on a commission-only basis.

No sales, no income.

Sure, some insurance agents did this in as client-friendly-a-way as they could, but nonetheless, making sales paid the bills. And anyone who grew up in that era knows plenty of unsavoury stories about mis-selling scandals or less than ethical behaviour.

As investment products evolved, financial advisers as they became known) moved from ‘merely’ selling insurance to selling a broader range of investment and pension savings products. And eventually, out of that evolution, came financial planning as many of us know it today.

But there remain cultural hangovers from the old sales-focused insurance industry.

In my opinion, one of the biggest is a deeply held belief in ‘incentives’ and the need for ‘variable remuneration’ when it comes to paying advisers.

The purpose of this white paper is to unpick and challenge that enduring belief. I hate it, and I’ve hated it for most of my time in the industry/profession, although early in my career I couldn’t quite put my finger on why.

We’re not running sales organisations that serve insurance companies anymore (by selling their products), we’re running professional services firms that work for the client – our clients.

Regardless of whether you love or hate incentives and variable remuneration, I’d like to make the case for a different approach to remunerating all team members inside your amazing financial planning businesses.

In my opinion, one of the biggest (cultural hangovers) is a deeply held belief in ‘incentives’ and the need for variable remuneration’ when it comes to paying advisers.

The purpose of this white paper is to unpick and challenge that enduring belief.

Why should you care?

Remuneration is a powerful signal that communicates what we value, what we reward, and how we define success in our profession.

In financial planning, how we pay our people says more about our firm’s culture and strategic intent than any vision statement ever could. Yet, for many firms, remuneration structures remain largely inherited from an outdated model: the sales-first, volume-driven culture of the old insurance world.

The belief in variable remuneration and incentives (commissions, bonuses, performance-based pay) persists, often unchallenged, and is seen as essential to motivating performance.

But what if that belief is misplaced?

What if the very systems we use to drive performance are actually undermining trust, collaboration, and long-term value creation?

What if clinging to sales-era compensation models is holding back the very progress we’re looking for, toward professionalism, client-centricity, and sustainable business growth?

This matters for anyone trying to build a modern financial planning business. One that genuinely puts clients first, develops talented people, and scales with integrity. If we want to elevate our profession, we need to examine not just what we do, but how we reward those who do it.

It’s time to ask some uncomfortable questions about how we pay people and to be open to better answers.

So here goes.

It’s time to ask some uncomfortable questions about how we pay people and to be open to better answers.

Why Business Owners Use Incentives.

In my work with owner-advisers I see two predominant reasons why they use incentives, or variable remuneration, particularly with their salespeople/advisers:

1. To minimise their fixed costs

2. To get people’s best efforts

(And if you hate the use of the word salespeople, forgive me, but in this part of my explanation I think it’s appropriate)

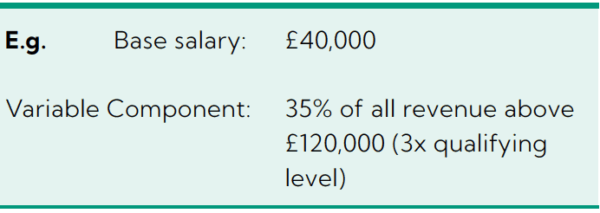

Most adviser remuneration schemes across our profession pay a small base salary and then reward advisers for a percentage of the revenue that they generate or manage.

In the business owner’s mind this is entirely sensible. ”I only pay for actual results”, they tell themselves.

However, ask yourself, “What’s the goal behind the goal?” 1

And the answer to that question I assume is that business owners want their advisers to perform at a high level, generating lots of revenue, from the right clients, and in a completely honest and ethical way.

Now ask yourself, does this approach seem like the best way to do that?

What I see in 90% of cases is newer advisers struggling along earning £60,000, when they really want to earn £100,000. They’re not happy.

The owner is also not happy. They want the adviser to produce the levels of revenue that would allow them to be paid £100,000 (from the right clients, and in a completely honest and ethical way), but typically it’s not happening.

With more experienced advisers who have a mature client bank, most of their revenue is ongoing (not new). In many cases these advisers feel they make enough money under this remuneration arrangement, so you could argue this is a disincentive scheme. And many business owners have moaned to me about advisers on this type of package who choose to work 3 days a week, rather than work harder to secure more clients.

There are other issues with this type of variable remuneration strategy too.

Effectively, it rewards advisers for generating more fees, which doesn’t always align nicely with a ’client-first’ approach.

What if the best advice is no action?

What if the business doesn’t want to take on a certain type of client, but the adviser tries to push it through to maximise their earnings?

What if the bonus is paid quarterly, and so at the end of each quarter, the back office team get harassed non-stop as advisers try to squeeze through as many cases as possible?

We know that all of these happen in advice firms.

What we have to ask is:

● What impact is that having on the rest of the team’s morale?

● Does it create an ‘us’ and ‘them’ dynamic in the business?

● What impact is that having on the “wholeof- business” effort to deliver for clients?

● What complexity is it creating as processes get short-cut or skipped? As we know, a shortcut now often creates a “management debt” somewhere in the future.

(Management debt is the extra work created in the future by taking short-term shortcuts today. A decision may seem expedient in the moment but often leads to greater complexity and effort down the line, which requires more work to rectify or sort out – i.e. the management debt.)

I realise some people can navigate these conflicts of interest, but I also know there are plenty who can’t and I wouldn’t want to take that chance if it were my business. This type of remuneration is certainly under the spotlight in the FCA’s Consumer Duty.

To genuinely get the best out of people is much more complex than simply putting in place some sort of incentive scheme or variable remuneration package. As the title of this paper suggests

“If incentives worked, we’d all be amazing by now”.

1 Reset: How To Change What’s Not Working by Dan Heath

Incentives do work…don’t they?

Here’s a snippet from the section above:

“The belief in variable remuneration and incentives (commissions, bonuses, performance-based pay) persists, often unchallenged, and is seen as essential to motivating performance.”

The key words are “often unchallenged”.

Many people who grew up in the sales era still hold the mistaken belief that incentives are the key to motivation.

Nothing could be further from the truth, and I’m going to challenge that right up front, because without a clear understanding of when incentives ‘do’ and ‘do not’ work, we’re simply going to be shouting back and forth at each other.

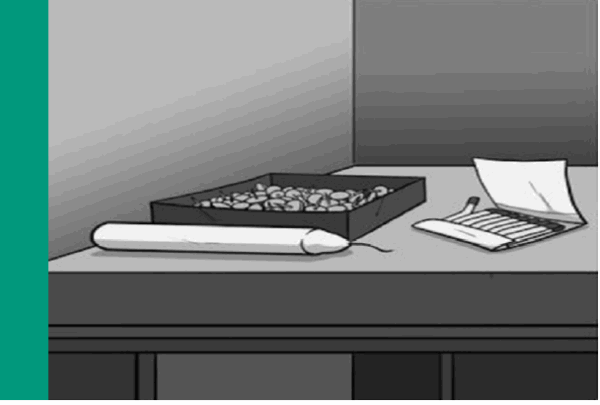

Dan Pink in his TED Talk – The Puzzle of Motivation, describes one of the more famous experiments around the question of “Do incentives actually improve performance?” – the candle experiment.

Participants are given a cardboard tray holding a bunch of thumb tacks, matches, and a candle. Their challenge is to attach the candle to the wall within a time limit. It’s an exercise in creative problem solving.

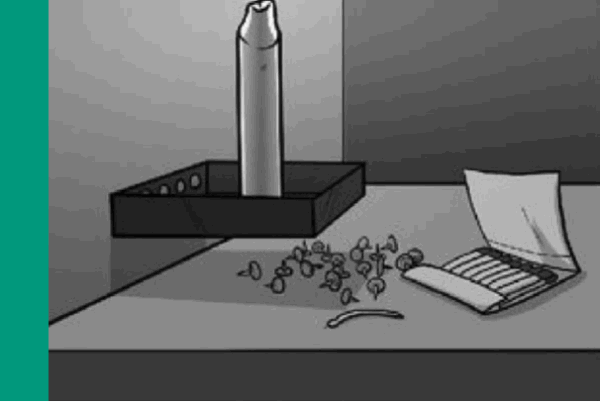

And to put you out of your misery, some groups tried melting the candle and sticking it to the wall, while others tried using the thumb tacks to pin the candle to the wall. Neither of these approaches works. The solution (staring each group in the face) was to tip the tacks out of the tray and tack the tray itself to the wall, and then stand the candle in the tray.

Apparently, many groups don’t see this use for the tray as it is holding the tacks, and they only see the tray in that use-specific context.

So, where do incentives come in?

In the experiment, different groups were offered different incentives to see if that would help them solve the problem faster.

What the experiment actually showed was that incentives often produce worse performance. Not only that, but different versions of these types of experiments around incentives have been replicated over and over and over for the last 50 years.

“This is one of the most robust findings in social science.” – Dan Pink

I’d encourage you to watch Dan’s talk now if you haven’t seen it. It’s entertaining as well as educational. You can click on the link here.

So what are some of the key takeaways?

“There is a mismatch between what science knows and what business does.” – Dan Pink

● It seems the business community as a whole (not just us in financial planning) really wants to believe in the power of incentives to improve performance, while all the evidence says exactly the opposite.

● There are some instances where incentives work, but they are very limited (and I’ll cover them in a second).

● Incentives seem to reduce people’s creativity.

Pink’s ideas were largely based on the work of psychologists like Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, who developed Self-Determination Theory (SDT). This theory posits that people perform best when they experience:

1. Autonomy – the urge to direct our own lives2

2. Mastery – the desire to get better and better at something that matters3

3. Purpose – the yearning to do what we do in the service of something larger than ourselves4

These are still seen as cornerstones of motivation in knowledge-based professions (like financial planning). Research 5,6,7 continues to show that:

● Performance-based bonuses can reduce intrinsic motivation, especially for tasks requiring judgment, nuance, and ethics (emphasis added).

● People working in high-trust, autonomy-rich environments tend to be more creative, ethical, and effective (emphasis added).

The words I’ve emphasised in bold are exactly the qualities and outcomes the owners of financial planning businesses are looking for as they assemble and grow their teams.

”The secret to high performance isn’t rewards and punishments, but that unseen intrinsic drive to do things for their own sake.”

Pink sums it up in his TED Talk:

“Those 20th-century rewards, those motivators we think are a natural part of business, do work, but only in a surprisingly narrow band of circumstances.

Those ‘if-then’ rewards often destroy creativity.

The secret to high performance isn’t rewards and punishments, but that unseen intrinsic drive to do things for their own sake.”

When do incentives work?

Just to get this out of the way right up front, incentive-based remuneration works best when the following 8 conditions are met8:

1. The role is repetitive and focuses on doing just one thing

2. The goals are unambiguous and one-dimensional

3. It is easy to measure both the quantity and quality of results

4. The employee has complete end-to-end control of process and outcome

5. Cheating or gaming the results are practically impossible

6. The role is very independent i.e. there is little or no need for teamwork or collaboration

7. The employee is not expected to help or support others

8. The employee considers the incentive as meaningful and the payout happens frequently.

In my opinion, a high-quality financial planning process doesn’t meet these 8 criteria. Not even close.

What’s been challenged?

Later research has added some nuance to Pink’s arguments by asserting, for example, that:

● Extrinsic rewards can coexist with intrinsic motivation if they’re framed as recognition or support rather than control.

● Fair pay is essential – without it, intrinsic motivation suffers. People need to feel valued and secure before intrinsic motivation can flourish.

● Team-based or long-term incentives (like profit-sharing or equity) are less damaging than short-term individual commissions.

● Incentives that are not tied to narrow outputs, but instead to values-driven behaviour or client satisfaction, can be more aligned with intrinsic drivers.

Now, before you get over-excited, I’m going to deal with some of these specific examples in this white paper too. I’ve seen a lot of attempts at getting team-based and long-term incentives right in financial planning firms, but there are always unintended consequences.

2 The explanations after each characteristic are taken from

3 The Puzzle of Motivation TED Talk by Dan Pink

4 The Puzzle of Motivation TED Talk by Dan Pink

5 Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic Motivation and Extrinsic Incentives Jointly Predict Performance: A 40-Year Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 980–1008

6 Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self‐determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362

7 Bazerman, M. H., & Tenbrunsel, A. E. (2011). Blind Spots: Why We Fail to Do What’s Right ` and What to Do about It.

8 Source: Scaling Up Compensation by Verne Harnish and Sebastian Ross. The Original source material is based on the work of Dan Ariely and other behavioural economists who study when incentives help or hinder performance.

Is There A Better Approach?

If you are trying to build an environment in your business that is high-trust, so your team can be more creative, ethical, and effective, and your team are performing tasks that require judgement, nuance and ethics (as I outlined earlier), then you really need to think long and hard about how you remunerate everyone on your team.

A fabulous resource you can lean on for all things remuneration is a book called Scaling Up Compensation: 5 Design Principles for Turning Your Largest Expense Into a Strategic Advantage by Verne Harnish and Sebastian Ross.

Many of the ideas I’m going to share with you in this white paper are based on their source material, with my own financial planning knowledge and experience thrown in.

Just to set the stage, here are two great quotes from the book:

“All people practices [i.e. HR practices], including compensation, need to create tangible value for the company’s stakeholders, especially for its customers.”

“How you compensate your people is one of the most important strategic decisions you will make. It can give you a significant advantage over the competition, support or hinder the culture of the business, and drive (or not) the behaviours you need to scale your organisation.”

One of Verne Harnish’s core concepts is this. When it comes to your remuneration strategy, “get it right and out of sight”. Then everyone in your business can focus on the real work of serving clients every day.

There are five design principles to consider9:

1. Be Different: Aligning compensation with culture and strategy

2. Fairness Not Sameness: Creating a coherent and flexible pay structure

3. Easy On The Carrots: Using incentives effectively

4. Gamify Gains: Driving critical numbers through p(l)ay

5. Sharing Is Caring: Getting employees to think like owners Let’s look at them one by one.

Let’s look at them one by one.

9 Scaling Up Compensation: 5 Design Principles for Turning Your Largest Expense Into Strategic Advantage.

Principle 1: Be Different.

Aligning Compensation with Culture and Strategy.

Your pay system should reflect your values and reinforce the right behaviours.

Here are a few interesting examples:

Example 1: Mini Movers

Mini Movers is an Aussie removals firm. One of their biggest costs (like all removalists) is insurance against breakages. The cost of cover can be anywhere from 3% to 10% of the job fee.

The owner of Mini Movers spoke with their team and said if we can move stuff and not break anything, we’ll save that insurance cost and I’ll share it with you.

The result?

A very careful, totally aligned removal team who get paid better than the industry average and a company with a great reputation for not breaking your stuff. It’s a win/win/win and came out of thinking strategically and aligning pay with the company’s values.

Example 2: Lincoln Electric

Lincoln Electric are a US firm that makes welded products. They’ve been in business for 125 years.

Workers are only paid for output, not time.

Off work sick? Don’t get paid.

Make a mistake on a job? Don’t get paid for that job.

And worse still, if a faulty machine gets delivered to a customer and it was your work, you might have to pay hundreds of dollars out of your own pocket to make it right.

In a busy week, you might work 60 hours. In a quiet week, it might be 30 hours, and you only get paid for what you produce in that time.

Sounds harsh, doesn’t it?

But when you look beneath the headlines, it’s one of the best paid manufacturing jobs in the world. Top-performers can earn over USD$100,000 pa (and the average income is USD$80,000 when Scaling Up Compensation was published in 2022).

If you stay for 3 years, you are given lifetime employment – a promise that’s been offered since 1948 and has never been broken.

The bonus to employees has been paid every year since 1934, and the company once borrowed $100M to make the bonus payment after a failed $84M foreign acquisition.

Does Lincoln’s approach to remuneration strategy incentivise behaviours in employees that customers appreciate?

You bet.

What do customers want? Perfect equipment.

How is the firm positioned in its marketplace? As a quality provider who stands behind the product.

What’s their internal culture? Personal ownership and attention to detail.

All three (perfect equipment, personal ownership, and attention to detail) mutually reinforce one another.

And just to put the icing on the cake, as a recruitment tool, it’s clearly going to attract staff who love the performance-based culture, and it’s going to scare off anyone who doesn’t.

Example 3: Mercadona

Mercadona is a Spanish supermarket chain. When French supermarkets moved aggressively into the Spanish market in the 1980s, CEO Juan Roig pursued a counter-intuitive strategy.

● He lowered prices for customers

● And increased wages for staff. (Salaries are double the minimum wage in Spain).

What was his thinking?

He believed that these twin strategic moves would:

a.) Attract more customers

b.) Attract better people to work in the business

Did it take some time?

It did. But over time, each strategy reinforced the other and “became like a positive spinning fly-wheel.” 10

By choosing carefully whom they hire and investing heavily in training and a Total Quality Management (TQM) approach, they are more productive 11:

● Sales per employee are 46% higher than the average US supermarket

● They outperform Walmart, the US giant, by a factor of 3x

What’s the lesson?

It’s easy to read about these unique approaches to remuneration and to want to copy them. However, that would be a huge mistake.

Principle 1 says…be different. It doesn’t say to copy someone else’s approach to remuneration.

These three examples were effective because they were tailored to their respective industries and crafted specifically to fit and reinforce the culture that the owners and leaders wanted to establish.

Another interesting idea that works in Financial Planning firms

In your own business, think of your people as an investment rather than a cost.

It was MIT professor Zeynep Ton who came up with the idea of a Good Jobs Strategy. This means paying significantly higher salaries than your competitors, whilst enjoying lower labour costs per unit and higher profits because your employees are more productive. The extra investment in your team generates behaviours that create a win/win/ win for customers, employees, and shareholders.

The Container Store (a US company) has a simple motto – “1 equals 3”. They believe that one good person can do the work of three average people, and so they hire and train for that and pay appropriately.

And in case you think this only works for low-wage jobs, Goldman Sachs pays double the rates of competitors, has less than half the employees on a per revenue basis and earns 3x more profit per employee.

Verne Harnish sums up the key takeaway:

“To be clear. The higher worker productivity at these firms is not the result of higher salaries (people generally don’t work harder because they get paid more), but the consequences of getting the best talent on board and creating an environment where these people can thrive and be their very best.” 12

This goes back to my earlier point that to genuinely get the best out of people is much more complex than simply putting in place some sort of incentive scheme or variable remuneration package.

“Worry about what people do, not what they cost,” writes Jeffrey Pfeffer in his classic Harvard Business Review (HBR) article Six Dangerous Myths About Pay.

“If you could reliably and easily measure and reward individual contributions, you probably would not need an organisation at all as everyone would enter markets solely as individuals.”

Jeffrey Pfeffer

Your unique culture and strategy in your business should influence your approach to remuneration and vice versa

Here’s a video of an Australian company, Atlassian, where the employees explain the values and what they mean.

(Warning: a little bit of coarse language in one part – they’re Aussies after all):

If you want to see smart remuneration strategy design in action, check out this article on the new collective bargaining agreement for the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) in the US. It’s a major departure from the traditional approach used by other major sporting leagues.

Check out these Six Dangerous Myths from Jeffrey Pfeffer. I’m sure you’ll recognise the mistake many businesses make around the cost of their staff.

TRUTH AND CONSEQUENCES: THE SIX DANGEROUS MYTHS ABOUT COMPENSATlON

MYTH |

REALITY |

| 1 Labour rates and labour costs are the same thing | 1 They are not, and confusing them leads to a host of managerial missteps. For the record, labour rates are straight wages divided by time – a Wal-Mart cashier earns $5.15 an hour, a Wall Street attorney $2,000 a day. Labour costs are a calculation of how much a company pays its people and how much they produce. Thus German factory workers may be paid at a rate of $30 an hour and Indonesians $3 an hour, but the workers’ relative cost will reflect how many widgets are produced in the same period of time. |

| 2 You can lower your labour costs by cutting labour rates | 2 When managers buy into the myth that labour rates and labour costs are the same thing, they usually fall for the myth as well. Once again, labour costs are a function of both labour rates and productivity. To lower labour costs, you need to address both. Indeed, sometimes lowering labour rates increases labour costs. |

| 3 Labour costs constitute a significant proportion of total costs | 3 This is true — but only sometimes. Labour costs as a proportion of total costs vary wildly by industry and company. Yet many executives assume labour costs to be the biggest expense on their income statement. In fact, labour costs are only the most immediately malleable expense. |

| 4 Low labour costs are a potent and sustainable competitive weapon | 4 In fact, labour costs are perhaps the most slippery and least sustainable way to compete. Better to achieve competitive advantage through quality, through customer service, through product, process, or service innovation, or through technology leadership. It is much more difficult to imitate these sources of competitive advantage than to merely cut costs. |

| 5 Individual incentive pay improves performance | 5 Individual incentive pay, in reality, undermines performance — of both the individual and the organisation. Many studies strongly suggest that this form of reward undermines teamwork, encourages a short-term focus, and leads people to believe that pay is not related to performance at all but to having the ‘right’ relationships and an ingratiating personality. |

| 6 People work for money | 6 People do work for money — but they can work even more for meaning in their lives. In fact, they work to have fun. Companies that ignore this fact are essentially bribing their employees and will pay the price in a lack of loyalty and commitment. |

Takeaways.

● Your pay system should reflect your values and reinforce the right behaviours:

● Remember, if you are trying to build an environment in your business that is high-trust, so your team can be more creative, ethical, and effective, and your team are performing tasks that require judgement, nuance and ethics, then you really need to think long and hard about how you remunerate everyone on your team.

● Maybe a great salary package does the job.

● And if you are worried about your own costs, I believe paying a great salary makes your decision-making very easy. If you pay well and someone comes in who can’t deliver to the standard, it’s a very easy decision to let them go quickly and start again on the recruitment.

10,11,12 Scaling Up Compensation: 5 Design Principles for Turning Your Largest Expense Into Strategic Advantage.

Principle 2: Fairness Not Sameness.

Creating a Coherent and Flexible Pay Structure.

Is it right to pay a 30-year-old adviser twice as much as the 45-year-old Operations Manager who effectively runs the whole business and manages a team of 12 people?

Will you have a rebellion on your hands if your new Head of AI recruit, with no people responsibilities, earns more than your most experienced and technically qualified paraplanner who manages 3 people?

Is it appropriate for your adviser, who is clearly best at converting new prospects into clients, to be paid more than an adviser who services an existing book of business generating £600,000 of annual revenue?

The challenge in small businesses is that remuneration systems have developed piecemeal over time, which means periodically they need to be looked at to make them coherent and fair.

Fairness, not sameness, means designing “a transparent and equitable system that allows for meaningful differences in pay between low, average, and top performers. Performance is not normally distributed, and thus pay shouldn’t be either.” 13

How do you make it work – where do you start?

There are two initial components of your well-designed remuneration strategy:

a.) A Total Rewards Strategy

b.) Equitable Pay

a.) A Total Rewards Strategy

When you are designing and eventually explaining your approach to remuneration, it needs to be a total rewards approach, not just salary. See the list of possible components below 14:

Possible Cash Components:

● Base pay (salary)

● Merit/Cost of living add-ons

● Short-term incentives (only if appropriate)

● Long-term value sharing

Possible Benefits:

● Allowances (e.g. car, living, relocation)

● Services (e.g. childcare), Insurance (e.g. income protection, health insurance, life insurance)

● Pensions

● Formal training

● Work/life balance (e.g. holidays, time off, sabaticals, home working, etc)

Relational Rewards:

● Recognition and status

● Employment security

● Meaningful and challenging work

● Informal learning opportunities

People won’t work harder because you increase their base pay. However, if you pay people below what they consider fair, it can be demotivational.

Compensation experts Zingheim and Schuster distinguish three elements that should help you design your base pay levels:

1. Competencies: Base pay should reward skills, knowledge and experience (not years of service). As new competencies are added, base pay can rise.

2. Sustained performance: Consistent and sustained performance should have the biggest bearing on base pay. Spikes or jumps in performance during short-term periods shouldn’t be a factor. You can recognise those periods of extra effort with non-financial recognition or a one-off variable pay reward (e.g. dinner or weekend away voucher or a small cash reward at the end of a busy period, like end of tax year).

3. Relative labour market value: Where do you want to set your own pay levels relative to the market? Will you “lead, lag, or match the market in terms of compensation” 15?

If you dive into this Total Rewards Strategy toolbox, you’ll need to communicate this really well to your existing team and any new potential hires looking to join.

Most discussions I hear about remuneration seem to get stuck solely on salary.

Now clearly, you might design a total rewards package no one wants. That’s not what I’m recommending. If a current staff member or potential joiner doesn’t value pensions or profit share, or private health cover, then you’ve wasted your money. So think carefully about all of the competing angles and what your employees truly value as you design your remuneration for each team member. A one size fits all approach won’t do the job.

You need to get base salaries right as your starting point, but don’t end there.

Base pay is not a motivational tool – it’s simply a hygiene factor. People won’t work harder because you increase their base pay. However, if you pay people below what they consider fair, it can be demotivational.

“In the startup phase, companies typically set salaries individually for each position, based on what the candidate asks for or what the business can afford. However, this approach can backfire once people find out what their colleagues are making. With increasing size of the company, you must introduce objective criteria for setting salaries. This is best done with a so-called pay structure.” 16

Creating your pay structure

To assign pay levels to different jobs, you need to establish criteria which are typically a mix of job-based and person-based criteria.

In small businesses your analysis of what a job role is worth needs to focus more on the person than the job itself because rapid growth can mean changing job roles and responsibilities, projects and assignments, making it much harder to assess abstract theoretical jobs.

Don’t get me wrong, there is a job-based element to it, but if you think of your best employees, they can jump onto a new creative project to help with whatever needs doing next.

In Verne’s book, they split pay grades differently for those in “leadership” roles versus “doing” roles. And they shared a process used by Sebastian Ross when he was at a medical company called TMC.

Leadership levels were based on characterisation developed by Ram Charan in his Leadership Pipeline framework:

Level 1 – Coordinator

Level 2 – Lead (role: leading others)

Level 3 – Head/manager (role: leading leaders)

Level 4 – Director/Executive (role: functional or business leader)

Level 5 – CEO (role: enterprise leader)

For people in “doing” roles, they used the following, inspired by work done at companies like Buffer, Medium and Fog Creek:

Level 1 – Trainee

Level 2 – Administrator

[Author’s Note: Not to be confused with the administration role in a financial planning firm]

Level 3 – Specialist

Level 4 – Pro

Level 5 – Ace

Level 6 – Wizard

Level 7 – Maestro

[Author’s Note: You might want to reduce the number of levels and/or re-name them to suit your own internal culture if you’re not as funky as Buffer, Medium and Fog Creek, but hopefully you get the idea]

The next step was to identify the criteria that define each level. They used five criteria and four values for each of them: (you might create your own criteria, but I include this as a guide)

1. Education: Formal education required to perform the job, not the education someone has:

● High school

● Bachelor’s degree or similar

● Masters degree

● Advanced degrees

2. Experience: Years of experience in other positions needed to qualify for the job:

● 0 – 2 years

● 3 – 5 years

● 6 – 8 years

● 9 – 12 years

3. Training: Time it takes in on-the-job training to become reasonably (80%) proficient:

● 1 – 3 months

● 3 – 6 months

● 6 – 12 months

● > 12 months

4. Time Horizon of the Longest Task: How far ahead the person regularly needs to plan to achieve the most important concrete results for which they are accountable:

● Daily to weekly

● Weekly to monthly

● Quarterly to annually

● Longer than 1 year

5. Scope of work: Describes the type of work and the way a person uses knowledge:

● Executional – carries out concrete tasks

● Operational – follows a process or methodology

● Tactical – determines the best way to meet goals

● Strategic – establishes plans, objectives, and policies

If you start trying to create your own objective criteria for setting pay grades, you may find that some past hires are significantly overpaid. Any outliers you have from the way you set salaries ad-hoc in the past can be considered “management debt” and hopefully resolved and aligned over time.

For example, perhaps you won’t keep raising pay as frequently or as much for any existing staff you feel are a little overpaid, based on your new objective criteria.

The pay ranges at each level should be fairly large to allow for merit-based raises without someone having to move up to another pay grade. This means that there could be a lot of overlap from one grade to the next.

For example, you could have a senior financial planner at L6 in the “doing” hierarchy earning £150,000 pa with no intention to become a department manager, while a colleague who has just been promoted to an L3 managerial role running the planning team earns £120,000. There’s nothing wrong with that.

“If you only pay to management responsibilities, you back yourself into a corner and only leave your people the option to compete for roles that don’t suit them, or worse, be promoted beyond their particular competency. Employees need to have attractive career options without necessarily ascending to the top of the hierarchy.” 17

Good communication is at the heart of this strategy.

b.) Equitable Pay

The second component of your well-designed remuneration strategy is equitable pay. You need to recognise the differences in performance among people doing a similar or the same job.

Think fairness, not sameness.

For unskilled jobs and semi-skilled jobs, the productivity difference between the best and worst performers can be up to 3x. For skilled jobs that can be up to 15x and even higher for highly creative jobs.

A good test for this is to consider how many average performers you’d swap for one of your superstars.

“Performance in most knowledge-based jobs is not normally distributed and the difference in impact between two employees can be huge.” 18

For example, in your financial planning firm, one administrator could be ‘good enough’ at their role, while another, very experienced administrator, is a superstar who can do anything accurately and fast.

The range of pay in your job descriptions for an administration role should reflect that. So in designing and communicating the pay range for the admin role you might say it’s between £18,000 – £60,000 pa. (Not in your job adverts, but in your internal documents and job specs).

You can put more detail around what knowledge, skills and behaviours you would see at different levels of experience and match the remuneration accordingly.

That range might seem ridiculously large, but you want to have the scope to reward high-quality people who might not necessarily want to move into a different role (e.g. administrator to paraplanner) just to earn more money.

In one financial planning firm I work with, the administrator is paid £70,000 a year but does the work of multiple, less experienced and less productive administrators in comparable firms.

You may never pay anyone £70k for an admin role ever, but your pay range should give you that freedom should you need to.

The same goes for an adviser role, and this is a classic case.

You might have two advisers doing ‘supposedly’ the same job. Both service existing clients and see the occasional new client. But one is clearly more skilled in new client acquisition (supported by data as well as observation). The servicing adviser might be on £x, and the adviser who can skillfully onboard new leads is on £2x or £3x.

When you explain the skill levels in an adviser job spec, you need to capture these nuances and show people what they can earn as they master each new skill (use ranges, not a fixed figure as I outlined for admin – for the same reasons). More qualifications, although important, are not the same as developing better skills.

By mapping this out in writing and explaining the skills required, you nip in the bud silly conversations about getting paid more money. People can see what they need to learn to earn at the next level.

Good communication is at the heart of this strategy.

And I hope it goes without saying that you should be investing heavily in training and developing your team.

Pay Reviews

Base salaries should be reviewed once per year for the whole business, ideally in line with your annual business planning and budgeting.

Don’t do anniversary-based reviews for each team member, otherwise, you will find yourself preparing for salary reviews with different people throughout the whole year. By doing it annually, you batch this task and for the rest of the 12 months, you and everyone else can focus on the real job – serving clients.

Valid reasons for an increase in base salary include:

● Increase in cost of living

● Increased responsibility or formal promotions

● Merit-based increase for sustained higher performance

● Adapting to changing market conditions to remain competitive

Length of service is not a good reason for a raise.

Consider setting up a remuneration committee with the senior leaders and one or two trusted front-line employees on it too. The view from the team members themselves matters because they decide ultimately if they think your remuneration system is fair or not. 19

Don’t hand out raises to make people work harder – you’ll end up disappointed.

“A raise is only a raise for 30 days and then it’s just what people earn.”

Dave Russo – former VP of HR at the SAS Institute.

A word of warning

As I said earlier, DO NOT copy remuneration strategies from other companies. You need to think about your own culture and values, and your own strategic challenges and design your remuneration around that.

Takeaways.

● Adopt a “Total Rewards” approach to designing your remuneration strategy

● There are three aspects to consider when setting base pay:

● Competencies

● Sustained performance

● Relative labour market value

● Base pay has to be right. And even though it doesn’t actually motivate anyone to work harder, getting it wrong can absolutely be demotivational.

● As your firm grows, try to get away from setting pay based on what the candidate asks for or what the business can afford. Move to a criteria-based system, albeit with broad ranges of salary at each level to acknowledge the differences between low, average, and high performers. Think fairness, not sameness.

● Don’t do anniversary-based reviews for each team member. Batch this task as an annual exercise so that for the rest of the year, you and everyone else can focus on the work.

13,14,15,16,17,18,19 Scaling Up Compensation: 5 Design Principles for Turning Your Largest Expense Into a Strategic Advantage

Principle 3: Easy On The Carrots.

Using Incentives Effectively.

Financial Planning firms are built on values like:

● Client first

● Caring

● Best advice

● Fiduciary

● etc.

Basically, do whatever is best for the client. Delivering that best advice is a whole-of-team effort.

To put an incentive scheme in place that rewards individuals for generating sales runs the risk of creating self-interested behaviour, which is in direct conflict with the company’s values. It makes no sense.

Key components of remuneration

While there are a lot of possible components to remuneration, there are two biggies:

a.) Base pay

b.) Incentives

We’ve looked extensively at base pay and how to set it in the previous section.

In summary, the thinking goes that if you pay great people great money, you can have fewer people. Your total employment costs will therefore be lower than your competitors’.

Incentives

Properly designed incentive programmes can impact employee motivation and performance. However, poorly designed ones (which are the ones I see most often) can impact motivation and performance too, but in all the wrong ways. I used the examples of Aussie removalist firm, Mini-Movers, welding manufacturer Lincoln Electric and Spanish Supermarket chain Mercador to illustrate that well-designed remuneration strategies can help deliver on your strategic priorities.

Another interesting example is the remuneration strategy at Egon Zehnder International, an executive search firm. They have three components to their remuneration:

a.) Base salary

b.) Partners get an equal share of profits

c.) And a final profit share gets paid based on a partner’s length of service with the company (i.e. you get paid more if you’ve stayed for longer).

[Author’s Note: This seems to fly in the face of the advice earlier in this paper. However, read on. While length of service is not a good reason for a raise in 99.9% of businesses, in Zehnder’s case, it’s specific to the strategy and culture of the firm.]

There are no bonuses or commissions paid for placing a candidate – none.

Partners are not paid on the size of their personal billings, unlike almost every other search firm in the world.

This distinctive model fosters close collaboration among the firm’s global network of over 500 consultants and reinforces a key pillar of their business philosophy: that enduring, trust-based relationships between consultants and clients are the cornerstone of success in executive search.

Clients are seamlessly referred to whichever office is best positioned to meet their needs. Unlike many other firms in the industry, internal competition or client hoarding simply isn’t part of Zehnder’s culture.

The downside of incentives

However, not all incentive schemes are as well thought out and aligned to strategy as the examples outlined above.

Variable pay, as opposed to base pay, needs to be re-earned in each pay period.

[Author’s Note: This is why the typical adviser pay structure – £40,000 basic salary + 35% of revenue over a 3x qualifying level – is not fit for purpose in my opinion.]

Financial incentives are meant to influence employee behaviour in three ways:

● Selection effect: They help people decide if they want to work at your firm

● Information effect: They tell employees what is important

● Motivation effect: They can motivate people to try harder (although we’ve challenged this idea earlier in this paper).

When you look at these three effects, I’m sure you can already start to sense that in a world that is changing very rapidly, designing incentives that create these effects and then keeps producing them time and time again is extraordinarily complex (if not impossible).

Incentive schemes have to be reasonably simple, otherwise they can’t be understood and actioned by employees. But if they don’t account for the breadth and nuance in most job roles, they don’t work either.

I love this excerpt from Six Dangerous Myths About Pay by Jeffrey Pfeffer:

“The head of North American sales and operations for the SAS Institute has a useful perspective on this issue. He didn’t think he was smart enough to design an incentive system that couldn’t be gamed. Instead of using the pay system to signal what was important, he and other SAS managers simply told people what was important for the company and why. That resulted in much more nuanced and rapid changes in behaviour because the company didn’t have to change the compensation system every time business priorities altered a little. What a novel idea – actually talking to people about what is important, and why, rather than trying to send some subtle signals through the compensation system!” [Emphasis added]

As many readers of this paper will know from their own experience, most incentive schemes don’t improve performance, they simply create unintended consequences that typically have to be unwound at some future point.

Unwanted side effects

If the incentive system is the dominant guiding force for a team member, they might push one goal over another to the overall detriment of the business.

For example, Verne highlights that “bus drivers in some countries… rewarded for punctuality, drive by a bus stop full of people during rush hour so they receive their punctuality bonus.”

In financial services, I’ve seen owners tear their hair out trying to get advisers to disengage from smaller clients (even one client) because adviser pay is calculated as a percentage of the revenue they manage. Asking advisers to shed a few low-value clients feels like you’re asking them to take a pay cut.

[Author’s note: I realise there are emotional issues too, but the potential loss of income, at least in the short term, is a major blocker.]

In another example, retail sales clerks have been known to hide popular items from their colleagues so they can sell them when they are back from their break.

And in large public companies, CEOs have been seen to backdate options to ensure they get paid.

Biases also come into play when trying to assess performance and pay

Personnel and teams guru, Marcus Buckingham, argues that as much as 60% of a performance review reflects the characteristics of the person doing the evaluation, rather than the person being evaluated. In other words, projection bias plays a major role, making the notion of objectively assessing employee performance far more challenging than it appears.

In another study, 97% of senior executives rated themselves in the top 10% of performers.

If we go right back to Dan Pink’s view of things, he’s not saying incentives don’t work, but that the conditions necessary for them to work are rarely found in the real world.

Do financial incentives work in sales?

Alright, alright I can hear you saying: But what about in a sales role – surely incentives work in sales?

Let’s put to one side the debate over whether being a financial planner is a sales role and make the assumption that when bringing new clients onboard there is a sales element to the process.

Dan Pink argues that financial incentives are just as useless for sales jobs as for any other occupation. Remember, in the candle experiment (and many variations like it), incentives reduced creativity.

The solution is not to incentivise salespeople, but to allow them to find their own intrinsic motivation for the work.

The argument goes that if someone doesn’t have a natural drive to sell and needs an incentive, then they shouldn’t be in sales in the first place.

I couldn’t agree more.

The best financial planners I know, love coming up with specific and creative solutions for each client they serve. The fact that they also get well paid is a happy by-product of the work, not the reason for the work itself.

In case you believe I’m some communist-like sympathiser who is merely driving an agenda here, I acknowledge that there is research supporting both schools of thought (i.e. some people do argue that incentives work).

In Verne Harnish’s book, there are some great examples of well-designed incentive schemes that delivered transformational results for the specific businesses that created them, whilst not hitting all eight of the criteria mentioned in this paper.

However, as I said earlier, do not copy remuneration strategies from other companies. The design of any successful incentive scheme in other businesses occurred because they built something to suit their unique culture and circumstances. They also tweak their schemes regularly to ensure they still deliver for the company.

If you think you’ve got the right formula for you and your business to implement and continually update an incentive scheme, then go right ahead and give it a try.

However, there are numerous examples out in the real world of incentive models being overused in companies and in situations where they are unlikely to work. On balance, I’d say that modern financial planning firms are customer-centric, team-based organisations, and therefore, incentive schemes generally will create more unwanted side-effects than positives.

The only exception might be profit sharing or having staff own equity in the business, but you need to be careful with those approaches too.

Across all industries, the Sales role is becoming less transactional and more complex. Prospective customers are likely to have done some research of their own online and become reasonably informed about product features and benefits.

Although, as all good advisers know, for most clients, a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. What clients need is someone emotionally removed from the problem, with the right knowledge and skills, to come up with the simplest solution that will meet their objectives. (There’s a reason why doctors are not supposed to treat themselves or their close family).

Many salespeople sell insights rather than just products or services. And most sales organisations are becoming more complex as they work hard to deliver more complete solutions for their clients. Salespeople are, therefore, often the conductors of the orchestra as opposed to doing everything themselves.

I think this is true for financial planners who often sit at the centre of the client’s advice hub, like a financial version of a General Practitioner doctor. When specialist advice is required, they know exactly who to get their client in front of, and can oversee the process, ensuring things don’t go off the rails.

Additionally, objectively measuring the individual performance of a salesperson is close to impossible. While I do understand that the adviser/salesperson is absolutely vital in the success or otherwise of securing a new client (and this would be reflected in their salary package), there are other people and parts of the process that are also important, which makes it difficult to add a variable remuneration component to the adviser as an individual.

In my view, in the financial planning context, extrinsic motivation via financial incentives won’t work, and companies need to fuel intrinsic motivation, which is more powerful and sustainable than extrinsic motivation.

And as I can vouch for from my own 20+ years of consulting with financial planners, none of the good planners that I know are motivated by money. Sure, everyone likes to earn well and be recognised in their field (including financial planners), but it’s not the driver. Good advisers are driven by the desire to make a difference to the people they choose to serve.

Make that the centre of your culture, and pay well, and you’re some way to creating an effective and sustainable business.

Takeaways.

● The values of a financial planning firm don’t often align with an incentive scheme that rewards individuals for generating sales. Delivering the best advice is a whole-of-team effort.

● When you look at the three effects incentives are supposed to have – the selection effect, the information effect, and the motivation effect – you can already start to sense that in a rapidly changing world, designing incentives that not only create these effects but then keep producing them over time, is extraordinarily complex (if not impossible).

● Incentive schemes have to be reasonably simple, otherwise they can’t be understood and actioned by employees. But if they don’t account for the breadth and nuance in most job roles, they don’t work either.

● Actually talking to people about what is important and why, rather than trying to send some subtle signals through the remuneration system, might be a better approach.

● Even for salespeople, the solution is not to incentivise them, but to allow them to find their own intrinsic motivation for the work, which in my experience, all good financial planners have in spades.

Principle 4: Gamify Gains.

Driving Critical Numbers Through P(l)ay

The example I used earlier of Mini Movers, the Australian removals company, and their “no-breakages bonus” is an example of a gain-sharing scheme.

These types of pay structures often involve teams, or even the entire company, rallying around a key metric that addresses a particular business challenge, sometimes with a gamified twist. Hitting the target unlocks a bonus that’s distributed once the goal is met.

The Mini Movers case stands out because it links the incentive to a real customer expectation – delivering undamaged items – and successfully translates that into reliable employee behaviour: treating possessions with care.

No free lunches

While I love the idea of some sort of focus on a metric to “gamify” things at work, it’s another idea that needs to be thought through carefully in my view.

In a financial planning firm, we might focus on one key metric like “client referrals”. I’ve often told my consulting clients that this one metric acts as a pretty good proxy for the overall health and performance of the business.

So why not make it our key metric? What could possibly go wrong?

Like in the bus driver example earlier (where drivers passed a bus stop full of people in rush hour to get their punctuality bonus), gamifying or incentivising the generation of client referrals, if done badly, could easily cross-over into behaviour that pisses clients off, rather than builds trust.

As with all of these ideas, it’s a very fine line between getting it right and getting it wrong.

Using Jeffrey Pfeffer’s idea, why not just communicate to your team how important it is to deliver an amazing whole-of-business client experience, which is the best driver of client referrals.

Despite what gets peddled around the profession, referrals don’t usually come from some slick one-liner asked by an adviser in a client meeting. And where a great one-liner does seem to work, you can probably find a business delivering an amazing whole-of-business client experience as the foundation underneath that.

Non-monetary rewards

Gain-sharing doesn’t always have to be tied to a cash payout. Non-monetary rewards can be just as powerful – if not more so. Think: extra time off, sabbaticals, unique project opportunities, professional development experiences (like attending a conference in an exciting location with a partner or family), upgraded travel perks, or simply hosting an unforgettable celebration for the team.

Studies show that these kinds of rewards often outperform monetary bonuses of equal value.

Why?

Because experiential rewards trigger emotional responses, and emotions help anchor memories. Most people won’t recall the exact figures on a payslip, but they’ll remember the feeling of being appreciated during that all-expenses-paid trip to the Caribbean. Although, if I was contemplating something that grand it would be an ‘after-the event’ thank you or reward for outstanding effort or results, not an ‘in-advance’ incentive scheme to try to improve motivation or performance.

What really motivates people?

We’ve all seen the studies that show what is motivating people at work. It’s typically a list that looks something like this:

Top 5 Workplace Motivators Today

1. Work/Life Balance & Flexible Work

2. Recognition & Appreciation

3. Career Development & Growth

4. Trust & Autonomy

5. Emotional Well-Being & Purpose

And while I’m sure all of these are correct to some degree for different members of your team, I came across some other research while reading a book called Reset: How To Change What’s Not Working by Dan Heath.

Teresa Amabile (Harvard Business School) and Steven Kramer spent years studying knowledge workers to figure out what really drives people at work. Their research, published in Harvard Business Review back in 2011, revealed something they called The Progress Principle. 20

In plain English? The biggest motivator for employees isn’t money, perks, or pressure, it’s making progress on meaningful work. Even tiny wins give people a lift. On days when employees felt they’d moved things forward, they were more positive, more productive, and more creative. On the flip side, setbacks hit harder than you might think, dragging down morale and motivation. What makes progress possible?

It’s not magic. It’s leaders creating the right conditions; providing support, resources, and the autonomy to actually get stuff done. Take the obstacles away and you unleash momentum, engagement, and long-term motivation.

To boil it down: when it comes to motivating your team, progress beats perks every time.

When we surveyed managers around the world and asked them to rank employee motivators in terms of importance, only 5% chose progress as #1,” said Amabile in a speech. “Progress came in dead last.” It’s a stunning oversight: The biggest motivator of employees is nowhere on the radar of the average boss.”21

Dan Heath

For the short version of Amabile and Kramer’s research you can read this article, The Power of Small Wins.

For the whole scoop, check out their book, The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work.

Takeaways.

● Is there one metric that sits above all others in your business that might allow you to gamify gains? I haven’t spent a lot of time on this point as I’m not sure it applies very well to financial planning firms. But maybe you think differently.

● Non-monetary rewards can be very powerful because they may signify recognition to the recipient, and the effect of any experience is likely to be remembered for longer. Although in a financial planning firm, non-monetary rewards might be more team-based than individual.

● Helping your team make progress could be the secret to creating an environment that people enjoy and want to be part of.

20 The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work, by Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer

21 Reset: How To Change What’s Not Working by Dan Heath

Principle 5: Sharing Is Caring.

Getting Employees To Think Like Owners

As a business owner myself, I love the idea of my team having some sort of stake in the business’s performance. However, in reality, it’s not always the brilliant incentive scheme it appears to be. The two options that spring to mind are:

a.) Profit sharing

b.) Equity

Profit sharing

Profit sharing may seem like a great idea to motivate staff and help build the business, but it can so easily go wrong. Let me explain.

If individual variable remuneration incentives are not so great in a financial planning firm, the business owner’s thinking often moves on to sharing the genuine profits of the firm with the whole team.

It sounds like a great idea and a no-brainer, but you need to be very careful.

Firstly, ask yourself the following question: Will your team be more motivated by a share of the profits?

Owners and salespeople assure me they will. I beg to differ.

My business partner and I considered something like this in my Australian financial planning business back in the day. We had two particularly amazing women working in our back office team, Brenda and Barbara.

Brenda had been an office manager in a large life insurance company, managing a large team. Later in her career, looking for an interesting but easier role, she became our receptionist and really was our ‘Director of First Impressions’.

Barbara, similarly, had worked at the same life insurance company in an administrative role. There was nothing she couldn’t wangle through the system to get our work completed and paid.

Because they were both so brilliant, we really wanted to devise an incentive scheme to reward the value they’d delivered to our small but growing business. We were truly grateful. However, after months of thinking about how to do this the right way, my business partner blurted out, “Brenda and Barbara already give 100%. It doesn’t matter what we put in place. They can’t give 110%”

So we abandoned the incentive idea and just tried to pay them what they were worth.

I realise now, 25 years later, that Brenda and Barbara were intrinsically motivated. They had personal standards, and this was how they operated in the world. Always had, always would.

I’ve come to believe that most people just want to come in and do a good job and be recognised and fairly remunerated for that work.

So pay people what they’re worth. Job done.

Could you incentivise another employee, who didn’t operate to the same personal standards as Brenda and Barbara, to change their behaviour?

I don’t believe so (and we sure tried over many years).

You are much better off spending your time and effort on finding people with that intrinsic motivation. You’re trying to hire patriots, not mercenaries. People who believe in the client-focused mission of your firm.

Secondly, an unintended consequence I’ve seen from profit share schemes is that owners can get pushback from the team when they want to hire more staff.

In the minds of the team, more staff means more costs, which means less profit to be shared now amongst more people.

This is particularly true when you don’t give the team access to the same information that you have (think full financial performance). Most owners don’t give the team access to all of that information, and so there’s a design flaw in the scheme from the start.

You complain that your team are all short-sighted when in reality, you designed a scheme they can’t ever fully understand.

And finally, sometimes the business doesn’t make great profits for a few years on the trot (as it invests in growth) and so the staff see the profit share plan as a waste of time at best, or a scam to diddle them out of more pay now at worst.

Now your incentive scheme has created negative outcomes, even though you did it with the best of intentions.

My advice?

Just stay away from incentives unless you can find a clear-cut case for it to align with culture, values and desired behaviours.

In a Financial Planning firm, the desired behaviours are:

● Do the best thing for every client

● Learn and grow as a person (skills, knowledge)

● Make a positive contribution to the team and the business

You hire people who possess those traits. You don’t incentivise people to behave like that. It doesn’t work.

Equity schemes:

If I were going to consider any type of incentive scheme, it would be some form of equity ownership in the total business entity.

This ticks a few boxes:

● It’s long-term (so we avoid incentivising the mercenaries)

● It’s outcomes-focused

● It’s a result of the efforts of everyone on the team

But again, ask yourself the question: Will this actually motivate anyone to do a better job?

You might choose to do it anyway from a fairness perspective, depending on your own personal views, but the impact in the short term at least, is unlikely to be dramatic. As more people accumulate more ownership, the impact on behaviour and thinking may well change and maybe that’s exactly what you’re after.

Here are some questions to ponder if you are considering an equity ownership scheme:

1. Who is eligible to buy or be granted equity, based on what criteria?

2. What structure will the scheme take – direct share ownership, options, or phantom shares – of what percentage of the company and how will the share be valued?

3. What are the tax implications for the business and the individual?

4. Will there be a vesting period (e.g. over 3–5 years) and what happens if/when someone leaves?

5. How can employees realise the value of the shares and can they be transferred or inherited?

6. Will there be different share classes and will employee-shareholders have voting rights?

7. How will ownership affect company decision-making and leadership?

8. What are the long-term cultural and motivational goals of offering equity?

As you can see, there’s a lot to consider and these bullet points are just the tip of the iceberg.

That means there is likely to be a lengthy period of thinking, discussion at leadership level, consultation with the team, as well as accounting and legal advice, to bring something to fruition. As a result, it’s likely that implementation of any equity ownership scheme will occur at the right stage of a firm’s development.

One example where giving an employee equity can be useful is where you have someone who is both giving you 100% and ambitious, and you want to retain them to step into your shoes. A stake in the business can stop them from looking around for their next opportunity and focus their energies long term on the business.

What I see in financial planning firms is that sometimes owners are a little too quick to want to give away equity (usually to certain individuals as a retention tool). However, as you can see from the list of issues to consider above, there’s a lot of thought that needs to go into this, and you might be looking for something that is for all team members. Sharing in the increased value of the firm is one way to align incentives.

Equity or profit share schemes are gestures of fairness and a way for owners to reward those who help generate profit and value in the first place. But remember, equity ownership and profit share schemes don’t increase motivation. But they may help employees think more like owners.

Takeaways.

● The first question to ask yourself is – “Why do I want to set up a profit share or equity ownership scheme? And will the team be more motivated by it?”

● Just stay away from incentives unless you can find a clear-cut case for them to align with culture, values and desired behaviours.

● In a Financial Planning firm, the desired behaviours are:

● Do the best thing for every client

● Learn and grow as a person (skills, knowledge)

● Make a positive contribution to the team and the business

● You hire people who possess those traits. You don’t incentivise people to behave like that. It doesn’t work.

● If I were going to consider any type of incentive scheme, it would be some form of equity ownership in the total business entity.

● Equity or profit share schemes are gestures of fairness. These types of schemes don’t increase motivation, but they may help employees think more like owners.

Conclusion

If you’re running (or building) a professional services firm that specialises in financial planning, I’m of the view that it’s difficult (maybe even impossible) to ‘incentivise’ high-performance through remuneration alone.

Many of our widely held beliefs around the power of and need for incentives are based on an enduring myth that flies in the face of 50 years of academic research. As Dan Pink acknowledges, incentives can work, but in a surprisingly narrow set of circumstances.

What if you just:

● hired the very best people you can find

● paid them what they are worth

● removed the obstacles that stop them from making progress each day

● worked hard to ensure they have opportunity to grow and develop, and to contribute to a mission they wholeheartedly believe in

Forget the incentives. Just focus on the real work of building a great team.

To paraphrase Herb Kelleher, the co-founder of Southwest Airlines:

● Happy staff…

● lead to happy clients…

● …lead to happy shareholders

It doesn’t work very well in any other order. If you build a business that people aspire to work for because of its culture of fairness and transparency, you’ll be building a successful business with longevity.

You don’t need incentives.

About Brett Davidson.

Brett is the Founder of FP Advance and Uncover Your Business Potential, a transformational coaching programme for adviser-owners who want to create world-class financial planning businesses. He helps great financial planners become great business people, so they can stay in love with their business and fulfil their potential.

Professional Adviser magazine rated him one of the Top 50 Most Influential people in UK financial services on three occasions – an honour backed by his robust “Little Black Book” of powerhouse contacts.

Brett’s mission: to wipe out the musty old “conflict of interest” model and turn the financial planning industry upside down, one firm at a time. He’s made great headway, having worked closely with hundreds of financial planning firms in the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, France, the Middle East, and South Africa, to make their businesses more fun, client-focused, and profitable.

Before coming to the UK, he was a partner in a leading Sydney-based financial planning firm and helped change it from a stodgy, commission-based insurance business into a breakthrough, ‘win-win’-style financial planning firm, before his exit at the end of 2003.

Personally, Brett is no stranger to ditching the status quo. In 2015 he and his wife Debbie sold most of their possessions, rented out their home in London and went travelling full-time, without their business skipping a beat. They were even featured in a piece in the New York Times, by Carl Richards from Behaviour Gap.

Brett has written regularly for some of the UK’s leading industry publications, including New Model Adviser, Adviser Business Review, Money Marketing, and IFA Magazine. His blog, full of inspiring free business tips, has the industry frothing for each weekly post.

His spare time is mostly sports time. He likes to keep fit with a little bit of boxing, some skiing in the winter and time at the gym. And at rest, he follows rugby, boxing, NFL and Formula One.

Occasionally he dusts off his 1995 Custom Shop Fender Strat to play with his band, The King’s Cats.

He’s married to Debbie who is Chief Executive at FP Advance.

You can follow Brett online and via social media:

Website: www.fpadvance.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/brettdavidson

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/davidsonbrett

Here’s how you can work with Brett.

Being a great financial planner doesn’t make you a great business person. But I can.

I’ve spent the last 20+ years of my life helping financial planners fall back in love with their business, to achieve personal fulfillment and transform the trajectory of their business journey.

It doesn’t matter if you’re in the final years of your career positioning for a sale, creating your own internal successors, or simply looking to continue the growth of your business – the work I do addresses the important underlying issues that make financial planning firms more valuable, more fun to own, and high-performing compared to their peers.

My signature programme, Uncover Your Business Potential turns great financial planners into great business people and creates the resilience that independently owned firms need to survive and prosper. It’s like an MBA for financial planners.